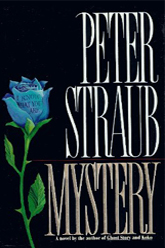

Mystery

Mystery, indeed. This dozy genuflection to crime and detective fiction, the genre least intrinsically suited to the arrogant breed of writers who, like Peter, disdain outlines, asks the reader to endure a hundred page introduction concerning irrelevant events of its protagonist’s (and, shamelessly, its author’s) childhood before settling down into a tale in which a gifted youth encounters an aged master detective and helps him solve both an ancient and a contemporary crime. One of the Hardy Boys meets Sherlock Holmes, that is the essential matter of MYSTERY. Again, our native city of Milwaukee is subjected to wilful and mean-spirited distortions, here taken to the extremity of its transformation into an anomaly-ridden Caribbean island. So incapacitating is the author’s laziness that he names his great detective, the “amateur of crime” standing in for Sherlock Holmes, “Lamont von Heilitz” and dares call him “the Shadow,” thereby invoking those halcyon afternoons when he and I huddled before the Motorola and rapturously absorbed the adventures of Lamont Cranston, known to crime-fighters and evil-doers alike as The Shadow, thrilling as one to that immortal mantra, Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!

The process which resulted in this exercise began with a far more interesting premise. Peter had relocated himself and his family in the overpriced brownstone on the Upper West Side of Manhattan where he resides to this day, and on a two-day layover between arrival in New York and the flight to the Seventh International Congress on Studies in Popular Culture in Prague, at which I would deliver the seminal paper on Barbie Doll, Betty Page, and Vampira: the Rage Engendered of the Genderized for which I was awarded my third “Atwood,” I availed myself of the Straubs’ hospitality, meaning that I was made to transport every single one of my bags, apart from those Peter found it in himself to transport for me, up five flights of stairs to the so-called “guest room,” where the weary “guest” slept upon a fold-out bed and enjoyed the use of an inconvenient bathroom sporadically provided with warmish water. This comfortless cell was located on the same floor as Peter’s office.

Grudgingly, my old friend took me to his favored watering holes after we had dispatched Susan’s minimal evening repast, and I could not but notice his uncharacteristic preoccupation, even after the consumption of a great many glasses of the potion he was drinking at the time. I believe it to have been a mixture of cognac and champagne known as a “French 75,” but I cannot be sure. These may have passed down the Straubian gullet on a later occasion, and he could have reverted at the time to gasohol. My enquiry as to his current project met with snarls, and after I had assisted him homewards and bade a fond good night to Susan, I made so bold as to sally into his office and rifle his papers in search of at least some clue to what he imagined himself to be writing. Papers I saw in great number, but these recorded only vestigial attempts at jump-starting a narrative. A foray into his hard disk – by this time I had been compelled to master the basics of “computing” – revealed more of the same, plus a great many of what I took to be elaborate jokes in the form of what I can only call faux-correspondence. I retired to the lumpy fold-out bed and the ungenerous bathroom in a state of the utmost concern.

On the following day, the hapless author informed me that he was indeed experiencing difficulties with his latest project and intended to address the problem by sequestering himself for a considerable period in a luxurious tropical resort. My alarmed reservations went unheard. Even Susan appeared to support her husband’s scheme, no doubt on the grounds that a ruinous plan was superior to no plan at all. We went our profoundly various ways.

Perhaps a month later, rather I confess a-tremble that I might hear of a crisis requiring my immediate appearance in Manhattan, I telephoned my old companion to be informed that his sojourn at “Jumbled Bay,” or whatever the place was called, had suggested a tale in the manner of Daphne du Maurier, whose autobiography he had stolen from the resort’s library. He would write a story of identical twins and Doppelgangers and bring it to completion within the year. My relief at this statement cannot be overstated. Surely, the design suggested to him by his tropic excursion would bring about a return to the first principles of straightforward narrative, especially as represented by the example of Dame Daphne!

One shakes one’s head, one shrugs one’s shoulders before the perversity of authors. After stumbling upon an entirely workable notion he should have clutched to his well-padded bosom, after actually committing theft in aid of the notion, within a few short months Peter blithely ditched Doppelgangers and Daphne du Maurier to assail the fortress of the mystery novel. It was his assumption that the conventional reader would comprehend his title to be a pun, and that the secondary meaning of “mystery” would inform this reader’s understanding of the book. One turns away from such delusions, remarking only that they are nowhere supported by the text.

Putney Tyson Ridge