Biography

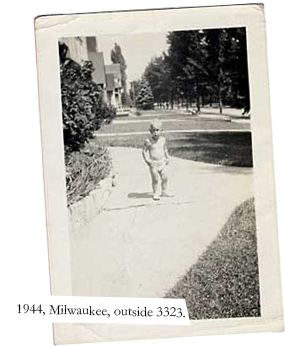

PETER STRAUB WAS BORN in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on 2 March, 1943, the first of three sons of a salesman and a nurse. The salesman wanted him to become an athlete, the nurse thought he would do well as either a doctor or a Lutheran minister, but all he wanted to do was to learn to read.

When kindergarten turned out to be a stupefyingly banal disappointment devoted to cutting animal shapes out of heavy colored paper, he took matters into his own hands and taught himself to read by memorizing his comic books and reciting them over and over to other neighborhood children on the front steps until he could recognize the words. Therefore, when he finally got to first grade to find everyone else laboring over the imbecile adventures of Dick, Jane and Spot (“See Spot run. See, see, see,”), he ransacked the library in search of pirates, soldiers, detectives, spies, criminals, and other colorful souls, Soon he had earned a reputation as an ace storyteller, in demand around campfires and in back yards on summer evenings.

This career as the John Buchan to the first grade was interrupted by a collision between himself and an automobile which resulted in a classic near-death experience, many broken bones, surgical operations, a year out of school, a lengthy tenure in a wheelchair, and certain emotional quirks. Once back on his feet, he quickly acquired a severe stutter which plagued him into his twenties and now and then still puts in a nostalgic appearance, usually to the amusement of telephone operators and shop clerks. Because he had learned prematurely that the world was dangerous, he was jumpy, restless, hugely garrulous in spite of his stutter, physically uncomfortable and, at least until he began writing horror three decades later, prone to nightmares. Books took him out of himself, so he read even more than earlier, a youthful habit immeasurably valuable to any writer. And his storytelling, for in spite of everything he was still a sociable child with a lot of friends, took a turn toward the dark and the garish, toward the ghoulish and the violent. He found his first “effect” when he discovered that he could make this kind of thing funny.

As if scripted, the rest of life followed. He went on scholarship to Milwaukee Country Day School and was the darling of his English teachers. He discovered Thomas Wolfe and Jack Kerouac, patron saints of wounded and self-conscious adolescence, and also, blessedly, jazz music, which spoke of utterance beyond any constraint: passion and liberation in the form of speech on the far side of the verbal border. The alto saxophone player Paul Desmond, speaking in the voice of a witty and inspired angel, epitomized ideal expressiveness, Our boy still had no idea why inspired speech spoke best when it spoke in code, the simultaneous terror and ecstasy of his ancient trauma, as well as its lifelong (so far, anyhow) legacy of anger, being so deeply embedded in the self as to be imperceptible, Did he behave badly, now and then? Did he wish to shock, annoy, disturb, and provoke? Are you kidding? Did he also wish to excel, to keep panic and uncertainty at arm's length by good old main force effort? Make a guess. So here we have a pure but unsteady case of denial happily able to maintain itself through merciless effort. Booted along by invisible fears and horrors, this fellow was rewarded by wonderful grades and a vague sense of a mysterious but transcendent wholeness available through expression. He went to the University of Wisconsin and, after opening his eyes to the various joys of Henry James, William Carlos Williams, and the Texas blues-rocker Steve Miller, a great & joyous character who lived across the street, passed through essentially unchanged to emerge in 1965 with an honors degree in English, then an MA at Columbia a year later. He thought actual writing was probably beyond him even though actual writing was probably what he was best at - down crammed he many and many a book, stirred by some, dutiful to the claims of others, and, more important than any of this, educated by the writerly example of his dear, eternal friend, the poet Ann Lauterbach.

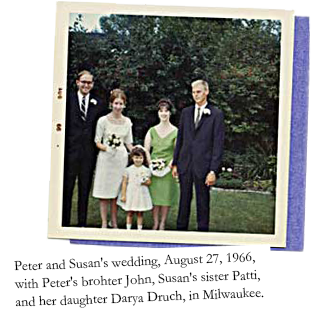

Stuffed with books and opinions about books but out of money, he married his beloved, Susan, took a job teaching English at his old school, now renamed University School of Milwaukee, and enjoyed a minor but temporary success as Mr. Chips-cum-jalapenos, largely due to the absolute freedom given him by the administration and his affection for his students, who faithfully followed him as he struck matches and led them into caves named Lawrence, Forster, Brontë, Thackeray, etc., etc. On his off-hours, he fell in love with poetry, especially John Ashbery's poetry, and wrote imitations of same. Three years later, fearing to turn into a spiritless & chalk-stained drudge, he went to Dublin, Ireland, to work on a Ph.D., secretly (a secret even to him) to start writing seriously.

Dublin, 1969-1972. His dissertation, a mess, devolved. He published poems in poetry places, did readings with new friend Thomas Tessier who was writing plays and poems, published two small books of poetry, Ishmael and Open Air, and finally surrendered to psychic necessity and wrote a novel, not at all a good novel, called Marriages, accepted by the first publisher to whom it was, heart in mouth, sent. He moved to the larger world of London.

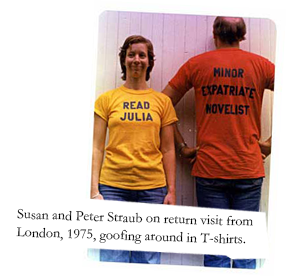

London, 1972-1979, Ann Lauterbach lived on the other side of Belsize Square; Thomas Tessier soon materialized, magnificently, as the Managing Director of a publishing house. He wrote & wrote & sometime in 1974, in desperation and despair first gathered up his ancient fears and turned them into fiction & by doing so saved his life. He and Ann talked about poetry, the mysteries of everyday life and everything else; he and Tessier talked about H.P. Lovecraft, No Orchids for Miss Blandish, and everything else, including the horror movies shown at the Kilburn Odeon. His writing improved. He and Susan bought a house on Hillfield Avenue in Crouch End, N8, and begat their first child, Benjamin, born during the writing of Ghost Story.

In 1979 he returned to America, living first in Westport, Connecticut, where Emma Straub was born, then in New York City, where he and his family inhabit a brownstone on the Upper West Side. He continues to enjoy the crucial friendships of Ann Lauterbach, Thom Tessier, and several others, mainly writers and jazz musicians. At some point he became conscious of the central issues of his life, which recognition made it impossible to cast them into the patterns, however imaginative, of horror literature, as least as conventionally regarded. Horror itself, on the other hand, has not abandoned him, nor can it ever, a matter for which he feels the deepest gratitude. He is a member of HWA, MWA, PEN and the Adams Round Table, and though he is without “hobbies,” remains intensely interested in jazz, as well as opera and other forms of classical music.

So matters stood in 2007-08, when (I think) the above was written. Since then, I have continued to live in my brownstone, though there are strong hints this may change sometime in the near-ish future. Books have been written, although these days what seems mainly to go on is rewriting. Seven or eight years ago, the Century Club endured a spasm of absent-mindedness and inattention, during the course of which they admitted me. It is the best club imaginable, with members who have actually accomplished things. (Boredom is not a problem at the Century.)

Somewhere along the way, I turned, rather to my amazement, into an old guy. Me…how’d that happen (I ask, in all innocence)? I lost a lot of weight, gave up alcohol, and grew a beard, so as to be prepared for the trials, infirmities, and indignities of ageing—also, I took up yoga, which whips my skinny butt three times a week.

My children are doing well, Emma as a flourishing young novelist, Ben as a sort of human-dynamo film agent. I am immensely proud of both of them, and grateful that I can be. My marriage is a lovely, solid relationship without which my life would be both impoverished and imperiled. One lives through so much, and after a while things sort of settle down, and most of what one wishes for is a long calm continuance, with work and love, friendship and art, clear-headedness, laughter, and an unbroken awareness of how fragile and threatened any such blessedness must be. As dear Ben Sidran says, Everything is broken, and nothing is gonna be all right. Cue the drummer.